Published: October 22, 2021

Lake Markham has written a very interesting review of Outlandish for Pilgrim House, exploring some of the book’s deeper themes and picking up on things that other reviewers haven’t. I’m really pleased he engaged with the book on such a philosophical level.

In Arthur Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation, he remarks that the permanence of a mountain seems to structure our understanding of the natural world, thereby conditioning the eye for worldly beauty. But what does it mean when the mountain begins to disappear?

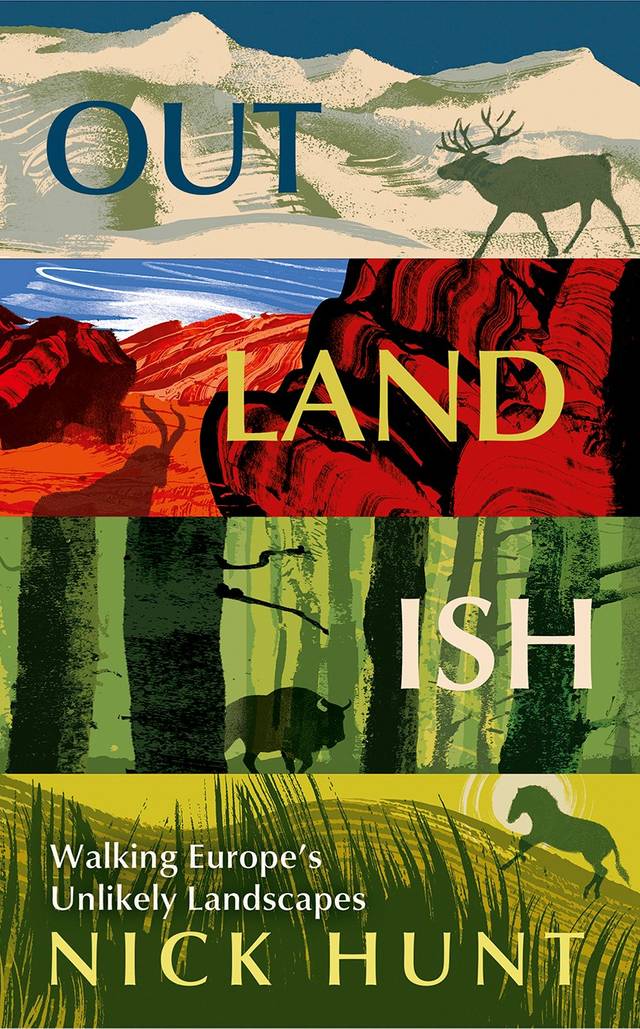

On its surface, Nick Hunt’s Outlandish offers a consolation for the apparent loss of this permanence—but it’s a much more nuanced consolation than that. While he does spend a significant amount of time on the effects of climate change, for much of the book he laments the erosion of our signs on the world, by which meaning—civic, geographical, existential—can be wrought. At the core of Hunt’s journey lies the observation that our aging planet, no longer structured by the sets of categories once applicable to it, is becoming comprehensible only in terms of the abstract. In Scotland he discovers a tundra, which he needs the concept of an exclave to explain. In Poland, he finds himself swallowed up within a jungle, finding his bearings by first tapping into the history of the trees, which grow in and among the story of the people. And in the badlands of Spain, he seems to transcend time altogether, an opportunity afforded by the desert’s unique ability to sustain life outside of its featureless terrain. Throughout his every twist and turn, each jaunt across a hand-drawn map, Hunt is surrounded by the slippages of a changing world, which nonetheless suggest something more permanent down below.

What Hunt pinpoints is that it’s not just our landscapes and biomes that threaten to shift to the polar margins, but it’s also our ways of understanding them, and in turn, ourselves. What is a desert, he asks, once its definition is outpaced by the very thing it was written to define? In place of indexable knowledge, Hunt instead offers up the observation that a desert is only a desert once it’s already been deserted—by plants, by animals, by the understanding. In its way, Hunt’s Outlandish is reminiscent of Jean Baudrillard’s America, in which another wandering European finds himself in a desert of signs where he feels out of place—America. In the book, Baudrillard details a continent rendered obsolete by the sheer profusion of its signs—a world which has become, as it were, a desert of meaning.

Yet things operate a little differently in Outlandish. There is still meaning to be found, fluttering flirtatiously at the horizon. Hunt even gives us the rule of thumb that, on level ground, that horizon is just about three miles away. However untenable, meaning in Outlandish is never exhausted completely, and it’s the endurance of life against difficulty—an endurance which Hunt himself demonstrates time over time—which gives meaning its strength. Whether it’s the inverse presence of Nazi symbols in Hungary—cutting directly through history to put the darkest hour in the same moment as our own; or it’s the spaghetti western sets of Spain’s Texas Hollywood, marking the theme park as both its own destination and origin; it’s the pregnant remnants of civilization which allow Hunt to reimagine his relationship with his changing planet, and in turn give himself purpose.

Outlandish isn’t so much a consolation for a meaningful world as it is for a world which sustains us as we furnish its meaning. While the future is dark, it’s the only place left to go—facing backward, gazing forever toward the past. The problem is that what’s behind us has grown difficult to recognize. Before a new nature, and without the proper tools to approach it, it’s this very pivot toward the brink on which Hunt turns. What is this place? he asks. Outlandish answers: “It has lost its name.”