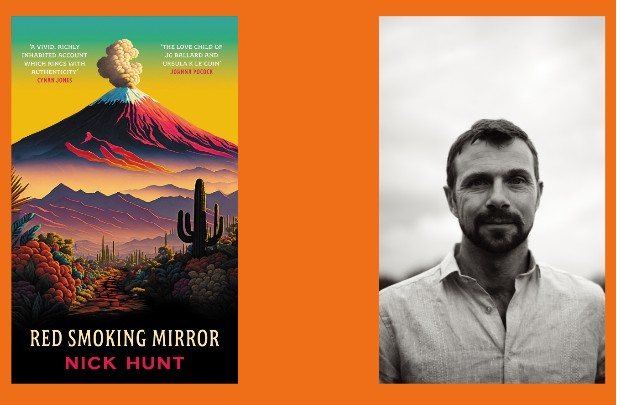

There’s an extract from the first chapter of Red Smoking Mirror in The London Magazine to give people a flavour of the book. Here it is (re)reproduced below.

She takes me by the hand and says, The smoke is on the mountain.

It is only cloud, I say.

It is more than cloud, she says.

We have come to the place of willow trees to watch the caravan depart. But the call has not yet come and so we watch the mountain. The mountain stands beyond the lake, its slopes rising bare and blue, the same parched colour as the sky. The lake is dull because the sun has not yet met the water.

We stand together looking up at the far naked peak. A foaming whiteness spews and rolls, clings to the mountain’s sides. My wife has younger eyes than I.

It is smoke, she says again.

Perhaps, I say.

She is seldom wrong.

Do you hear it speak? she says.

We stand together listening. I do not hear the mountain. All I hear is the morning wind, the cry of a bird I cannot name, the gentle lapping of small waves against the floating gardens.

No, I say.

It is sleeping now. But it spoke last night, she says.

My wife goes to the waterside and dips her ankles in.

The water’s skin appears to flinch as if it is repulsed. She tweaks the hem of her white dress and steps a little deeper in. Bright bubbles break the surface.

It spoke while you snored, she says, without looking back at me. The water laps her calves, her knees.

Not too far in, I say.

I am mistrustful of the lake as I was mistrustful of the sea. For a man who has drifted far I do not like the water. A mountain does not speak, I say, correcting her as I do with declining frequency these days. A mountain rumbles, booms or roars. It does not possess a voice.

Everything speaks, she says.

Thigh-deep now, her dress held high, she wades along the shallow shore. The floating beds are fulsome with crops before the harvest. Idly, as if thoughtlessly, she snaps off a cob of maiz and proffers me some yellow grains.

When I shake my head she shrugs and casts the maiz on the water.

A mushrik boy is watching us. Bare-footed, with a shaven skull, six or seven years of age, he is lurking in the trees where the road forks to the city gate. He might be hunting rats or water-gods.

I smile and call a greeting.

At first I think I am the cause of the fear on his face. I am used to this. Such fear is innocent. But his eyes are on my wife and the maiz floating on the lake. That wanton, wasted offering.

My wife’s gaze fixes on him.

The child appears caught in fright but my wife speaks a word I do not know, something sharp that releases him, and he vanishes among the trees. The maiz bobs up and down. Ripples slowly spread from it, rolling out across the lake. I feel uneasy watching them, as I do increasingly.

Men are made of maiz, she says.

We are made of dust, I say.

Water glistens on her shins as she wades back onto shore. A slimy stripe of green weed is stuck between her toes. My eyes climb to the peak again, to the cloud-smoke bulging from its snout.

My man of dust, says my wife.

And with that I am joyful.

The rising sun has cleared the hills. Light spills across the valley. The dark lake turns to silver shards, scintillating blindingly, and the ripples from the broken maiz portend nothing more than peace rolling out across the world, its circles ever widening. The two of us are standing here at its very centre.

I am happier here, a foreigner, than I have been anywhere.

We stand together in the light. Her hand joins my hand.

Then from behind us comes the call, a single ululating voice, followed by the clash of drums and the twang of stringed instruments, and then the cries, the groans of beasts, the clattering hooves, the dust, the din.

We turn towards the city gate. The caravan is leaving.