REVIEW OF ‘THE BOOK OF TRESPASS’ BY NICK HAYES

Published in Dark Mountain

December 2020

As someone who does a lot of long-distance walking, often with – ideally with – as little planning as possible, I have often slept outside. And every time I have slept outside, I have found myself engaging in a conversation with the landscape. Choosing the right spot involves a kind of bargaining, a negotiation between invading somewhere and belonging. In this field? Too exposed, you can be seen from every side. In those woods? Too sinister, it’s like you’re trying to hide. Here? No, that just feels wrong. How about this riverbank? Yes, a riverbank is good. On this riverbank with the woods at my back? That feels right, you’re sheltered behind but have a clear view in front. The sound of the river will mask your noise. I feel I have a right to be in this place. Well, technically you don’t. But let’s not worry about that.

After my tent is up, or my bivvy-bag unrolled, the process of settling in involves further dialogue. I am a stranger to this place and this place is strange to me, and both of us must undergo a process of acclimatisation. This is often awkward, sometimes uneasy, occasionally alarming. An angry dog is barking somewhere. It’s in a village far away. There are empty beer cans under the leaves. Kids come here sometimes. That sounds like… footsteps through the trees. Not a person, an animal. It sounds big. It probably isn’t. A rat, a ferret, a fox. I can hear it breathing heavily. It’s a wild boar, perhaps. Are there wild boar here? Maybe.

After that period of adjustment comes a moment of relief, when these anxious exchanges stop. The voices hush; mine and the land’s. Everything stills and settles. The insects, the birds, the trees – the genius loci, spirit of place – have habituated themselves to my presence, and I am no longer quite so strange. It feels as if I have been accepted, as if I have been allowed in.

The thing that has always struck me most about walking, sleeping and waking up where I am not supposed to be – the thing about trespassing – is that, crawling from my tent, or my pile of leaves, the next morning, stiff and sore but satisfied, having slept the night unscathed, what I have often felt is a sense of paradoxical belonging. As if the act of sleeping here has given me a right to the land that I did not have before.

Another way to describe this feeling is ‘entitlement’.

The word is weaponised these days, and in one sense I am entitled in the pejorative sense of it; white and male, I can trespass in many places with a relative lack of fear that might be incomprehensible to other people. But, in a much older sense, the term is accurate. ‘Entitler’ comes from Anglo-French, and refers to the act of bestowing a ‘title’, or proof of ownership, on the newly minted owner of an estate or property. To be entitled is to have land, and to keep others off that land. Like many things about our relationship – or lack of one – with the land today, the word has its roots in the Norman Conquest, when William the Bastard claimed England as his personal property and parcelled it up as gifts and bribes for the violent knights who had helped steal it.

This is a starting point for The Book of Trespass: Crossing the Lines that Divide Us, by graphic novelist, illustrator and writer Nick Hayes. The book is structured around a series of trespasses undertaken by the author, often in the company of a friend, onto some of the 92 per cent of England (and the 97 per cent of rivers) from which the public is excluded by trespass laws. These laws are, as Hayes tells us early on, civil rather than criminal – the warning ‘Trespassers Will Be Prosecuted’ is quite simply untrue – but the book’s publication coincides with a Tory proposal to make trespass a criminal offence, which would impact on everyone from Gypsies and Travellers to members of the Ramblers’ Association. This is only the latest twist in a thousand-year plot to bully the commoners off the land and concentrate power in the hands of the wealthy, and Hayes is angry about it. This is not so much a book about trespass as a call to tear down walls.

‘If you think England is beautiful, you should look behind its walls.’ Throughout the book, Hayes does this with relish and panache. During the course of his transgressions – a word, as he points out, with moral as well as physical connotations – he takes the reader on journeys into landscapes that are, by definition, normally hidden from public view. Much of his research necessarily involves sneaking around some of the loveliest portions of private land in the country, from Hampshire’s Highclere Castle (where they filmed Downton Abbey) to the estate of former Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre. There’s an often surreal contrast between the chocolate-box perfection of the places he encounters — the quintessence of mannered, civilised Englishness — and the ever-present threat of being apprehended. Trespass may (for now, at least) only be a civil offence, but the notorious Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994 – the same piece of legislation that turned ravers into criminals – raised the stakes with the invention of ‘aggravated trespass’, in which the meaning of ‘aggravated’ is conveniently vague. As Hayes writes, ‘if you are doing something that is not illegal (photography, dancing, playing the flute), while doing something that is not criminal (trespassing), you can be automatically arrested, and liable to six months in prison and a level-four fine.’ There is more jeopardy in these walks across bucolic country estates than in most other travel writers’ treks through the wilderness.

When he hops his first wall, Hayes crosses an invisible line not only onto private land but – as if crossing a mythical threshold – into another mode of existence. He has become a vagrant, a category of undesirable conjured up by a legal system that ‘sought to criminalise not anti-social actions, but, rather, a state of being, a social and economic status, a type of person.’ As well as being a gripping history of land ownership in England – a journey that leads from the Norman invasion through medieval peasants’ revolts and the land-grabs of the Enclosures all the way up to Greenham Common and the eruption of Occupy – The Book of Trespass is an attempt to shatter what Hayes calls ‘the mindwall’, an internalisation of ruling-class power so effective we don’t even see it. ‘The wall presents itself as a blank statement of authority, and we obey it because we see it without its context. The mindwall has become so entrenched in our heads that it remains unchallenged and unquestioned.’

In breaking down that mindwall, Hayes strays far from the theme of trespass into what land ownership – and the violence inherent in that concept – represents on a psychological and even a spiritual level. Once the veil has fallen away there’s no coming back from it: England’s green and pleasant land is transformed, as if by the breaking of a charm, into a darkly violent place whose loveliness stems from massacres, rapes, genocides, counter-insurgencies, witch-burnings, Clearances and ‘improvements’ that, for hundreds of years, have stolen the land from under people’s feet and cemented aristocratic power.

Most disturbing are the links between country house wealth and slavery – the brutalisation of Africans laundered into neo-classical architecture – and the ransacking of India over the centuries of British rule, during which the subcontinent’s GDP shrunk from 27 per cent to 3 per cent. ‘The railways that Britain “gave” India were … in fact intravenous tubes lodged deep inside the body, transfusing the blood as efficiently as possible from the heart of India to England’, writes Hayes. Similarly, through his eyes, the picture-postcard mansions so beloved of the National Trust transform into ‘what the Germans call Mahnmal, monuments of deep-set national shame. These gleaming, cream-stoned treasure chests, stuffed to the eaves with violent plunder, are in fact radiant monoliths to the myth of white supremacy.’ There is more than a touch of folk horror to this lifting of the mask: the arcadian idyll underneath which lurks pure evil.

Amidst the horror, though, is hope. For the land is awakening. What makes this book much more than a well-researched investigation of land injustices in England, or a lyrical journal of transgressions, is Hayes’ belief in the magic that exists in the rivers, hills and woodlands from which we have been excluded. Years ago, camping in Scotland – a country in which the freedom to roam is enshrined in law – the author lay awake till dawn listening to the belling of stags, ‘a haunting, powerful noise from the animal kingdom, a raw, timeless awakening to the world outside human ken. In Scotland, this magic is my birthright. In England, it is a crime.’ This ‘magic’ is partly proven by science – at the end of the book he dutifully touches on nature deficit disorder and the mental health benefits of immersion in greenery – but the book’s heart is a wild howl from somewhere much more primal, as voiced by Johnny ‘Rooster’ Byron in Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem.

From breaking down the walls of the mind with magic mushrooms in Epping Forest and ecstasy in Oxfordshire (performing an ‘inverse trespass’ by busting out of the steel enclosure of the upmarket, and misnamed, Wilderness festival) to risking a year’s imprisonment on a mission to find the Herne Oak, associated with the anarchic freedom of the Wild Hunt, Hayes leads us on a quest to gather that magic back. The book is an invocation, a counter-spell to the dark enchantment that keeps the vast majority of us in (or out of) our place. In crossing the line, we might rediscover our own genius loci.

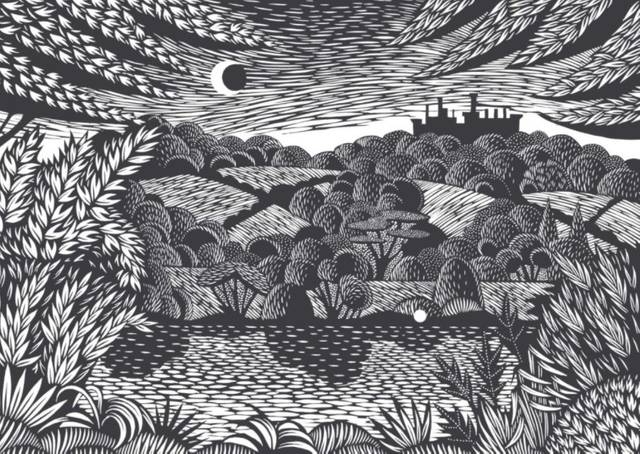

Illustration: ‘Belvoir Lower Lake, Belvoir Castle, Leicestershire’ by Nick Hayes