September 2009

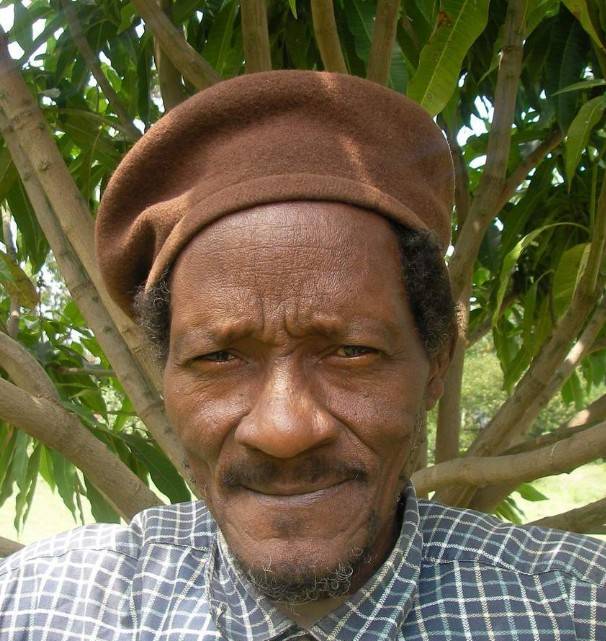

Donald Fullwood left Jamaica almost 30 years ago to start a new life in Shashamane, Ethiopia. A devout Rastafarian, he was following in the footsteps of the Rasta pioneers who came here to settle the land granted them by Emperor Haile Selassie, who they worshipped as an incarnation of God. He lives in a bare breezeblock house, tending a small garden that grows potatoes, corn, carrots, peas, scotch bonnet peppers, mangos and strawberries. ‘There was nothing here before,’ he says as he leads me around. ‘But when Haile Selassie gave us this land he said we must be productive, to utilise and develop it for the welfare of our community. And he said we must live in love, in parallel with Ethiopian life. Ethiopians and Jamaicans are blood brothers.’

Donald came here on his own, leaving his family behind. He raised money for the migration fee by dancing. He regards it less as a move to a new land than a spiritual ‘repatriation,’ a return to ancient roots, following the ‘back to Africa’ call of black spokesmen like Marcus Garvey. ‘We read the Bible, particularly the Book of Exodus. It states that we should find our brothers. I came to know Ethiopia as the true womb of Christ, a place where Christ-like people live. It was a catastrophe that brought us to the West. Now we have returned to our rightful place.’

The cult surrounding Haile Selassie – Ras Tafari, the Lion of Judah – was born from a legacy of oppression. For Jamaicans living under the thumb of the British colonial government, whose ancestors had been brought to the New World in chains, Ras Tafari symbolised many things: a powerful and respected black leader, ruler of the only African country to successfully fight off colonisation, and, in his claim to be a direct descendent of King David, the heir to ancient Biblical power and wisdom. Despite pressure from British authorities attempting to curb the rebellious new movement, the Emperor neither confirmed nor denied his divinity during his reign. When he visited Jamaica in 1966 his plane was met on the runway by thousands of jubilant Rastas. A decade before, he had made a gift of 500 hectares of crown land to followers of the rapidly-growing religion.

Since then the Shashamane community has expanded from 12 founding families to about 200 families from all over the world. But life in this long-sought spiritual homeland has proven far from easy. Haile Selassie was deposed in a military coup in 1974, and the hard-line socialist regime that followed reduced the community’s land from 500 hectares to 11. That regime fell in 1991, but the current government has pursued a confused policy towards the settlement, by turns reassuring and threatening it, and the community now exists in a bureaucratic limbo. Members talk of land confiscation, persecution by the police, and threats by the local government to bulldoze their houses.

‘I tell you, man, it’s miserable,’ says Donald. ‘They do some horrible things. They are trying to suppress our way of life. Rasta land has been confiscated, and at the same time they want us to have more money for tax. Our biggest interest is to have legal entity with the government. We desire a proper Jamaican ambassador to protect our rights. We want someone who can feel and know the pain we go through.’

A further problem, even more worrying to those who see this place as their salvation, comes from within the community itself. The popular image of Rastafarianism has created a new generation that flocks to the lifestyle of reggae and ganja, but shows little interest in the ideals – or religion – on which the settlement was founded. Donald, as one of the elders here, fears that the community’s true mission is in danger of being lost. ‘The spirit of Shashamane has changed. Everyone is material now, everyone wants money. The young people don’t want to work. They are selfish and greedy. They don’t worship God properly. There is much disrespect for authority, disrespect for people.

‘We left Jamaica with a religious consciousness, otherwise known as zeal. But if we don’t see it being established in reality, it’s a degraded covenant. The dream needs humbleness. It needs a renewed sense of consciousness that God is with us.’

And how are the Rastafarian settlers viewed by the local population? It’s fair to say that most Ethiopians – themselves either Muslims or Orthodox Christians, as Haile Selassie was – are perplexed by the worship of their former emperor, who presided, after all, over a feudal and autocratic state, and even tolerated slavery in the early part of his reign. ‘The Orthodox Christians don’t understand,’ says Donald. ‘They refuse to discuss the subject of the continuation of the Davidic kingdom. They don’t recognise our religion, they only see ganja and dreadlocks. We don’t want to have a criminal stigma. We don’t want Ethiopians to feel that we are cattle down here, eating ganja for our lunch. Rastafarianism is not a threat. It’s about the behaviour of the individual. It’s not about mind control. It’s about how this present generation is going to face reality.

‘I have happy memories of Jamaica, but I don’t want to return there. Too much violence, thieving, murder. I don’t even like to hear about it. Despite all our problems, Ethiopia is better. I believe this is our true home. It’s our promised land, in reality. But I still want things to be better.’

One hundred and fifty miles to the north, in the capital Addis Ababa, lawyer Ato Eshetu Mamo also talks of a promised land. But for him, the path to his spiritual home leads out of – not back to – Africa. Eshetu is a member of the Beta Abraham, which, along with a larger community called the Beta Israel, are the remnants of Ethiopia’s ancient population of black Jews.

Known as Falasha by other Ethiopians – a term that translates roughly as ‘exiles’ – the Beta Abraham and Beta Israel practice an ancient form of Judaism that has stayed largely unchanged since Old Testament times. Scholars disagree on whether these groups are the descendents of Jews who migrated to Africa, or the descendents of African converts to the Jewish faith, but either way Judaism has played a major role in shaping Ethiopian history. The Ark of the Covenant itself, the ultimate symbol of the Israelites, is believed by most Ethiopians to reside in the Orthodox church in Axum.

‘Before we came, there was only paganism. After the tribe of Judah was established, the Ethiopians turned to God,’ says Eshetu from behind his desk, which is covered with books on legal matters and texts about Judaism. He is an articulate and passionate speaker, accompanying his words with emphatic hand gestures. ‘In the past, the Jews were the kings and rulers of Ethiopia. The Christians stole everything from us. The Orthodox church is really Jewish culture. The Old Testament is ours. Even the Ark, which came from Jerusalem, they took from us and kept as their own. Whenever you think of Ethiopia, you are really thinking of Israel.’

After being displaced by the rise of Orthodox Christianity, Ethiopia’s Jews retreated to the remote highlands of the north. In common with Jewish people worldwide, they endured centuries of persecution. Many pretended to convert to Christianity, but continued to practice their faith in secret. ‘The Christians said the Jews were evil, that they ate people with their eyes. Still there is discrimination. The situation has improved in recent times, but still people don’t look on Jews as human beings. Even now we are suffering. Whenever I think of this, I can’t control myself.’

After receiving belated recognition from the authorities in Jerusalem, Ethiopian Jews were granted the right to ‘return’ to Israel in 1975, a process known in Hebrew as ‘Aliyah.’ Since then, many thousands have made the long journey back to what the Bible tells them is their birthright. During Ethiopia’s civil war, the Israeli air-force carried out the audacious Operation Moses, secretly airlifting thousands of Jews to Israel from the deserts of Sudan. The exodus later continued under the codename Operation Solomon, which saw over 14,000 make the journey. Today a mere 10 or 15% of the country’s former Jewish population remains, mostly waiting in Addis Ababa for their applications to process. The procedure takes longer than an air-lift now. Emigrants must submit proof of their Jewishness through the maternal line, and organise their future housing, schools and employment. The process can take a very long time. Some have been waiting in Addis Ababa, supported by aid organisations, for up to 12 years.

‘This isn’t economic migration. It’s based on our faith,’ says Eshetu. ‘It’s about identity. Jews must get to Israel in order to know who we are. All Jews must be restored to Jerusalem. This is the word of God. I believe in the prophecy of the Third Temple. The chosen people will return to Zion. That’s why we Jews are living in hope here. The God of Israel will emancipate us from the persecution we have suffered. ‘The Orthodox Christian kings of Ethiopia all claimed Judaic descent. Haile Selassie said he came from the line of Solomon and David, but we’re the ones who really come from the tribes of Judah. Haile Selassie persecuted us worse than anyone. Up until now, we have been slaves. In Israel, we will be free.’

Donald and Eshetu both come from communities that have suffered centuries of inequality, having been displaced from an ancient homeland. The legacy of slavery has shaped their religion and culture. Both are part of a diaspora: one outcast in the Caribbean, seeking return to Africa, one outcast in Africa, seeking the Middle East. And whether their epic journey is termed ‘Aliyah’ or ‘back to Africa,’ both see their people’s salvation in a return to long-lost spiritual roots.

Most strikingly, both narratives are suffused with the language of the Old Testament: both talk longingly of a return to Zion. For Jews, Zion is the Holy Land to which they must be restored, the concept which gave birth to the Zionist movement. To Afro-Caribbeans in the 1930s and 1940s, reinterpreting the Bible to make it relevant to their own experience, ‘Zion’ came to mean a return to their mystical, African roots; just as ‘Babylon,’ as one of the enemies that persecuted the Israelites, became a cipher for colonial oppression, and the polluting influences of materialist culture. The Beta Abraham and Beta Israel believe they are descended from the Tribe of Dan, one of the Twelve Tribes of Israel who were dispersed around the world. Within Rastafarianism, the Twelve Tribes of Israel is the name of a prominent ‘mansion,’ or branch, illuminating the supposed link between King David and Haile Selassie, the self-styled Lion of Judah. Both Rastafarians and black Jews see themselves as bearing the torch of the Davidic lineage, the physical or spiritual heirs of that divine power.

The experience of both communities also shows that the promised land can be far from paradise. When Rastas came to Africa they experienced suspicion and hostility from the governments that came after Haile Selassie, and the general incomprehension of the local population. Ethiopian Jews, in turn, face hardships in Israel. Leaving aside the small matter of the Palestinian conflict, many report discrimination from longer-established Jewish groups, which leaves them at the bottom of society with bad housing and menial jobs. Ironically, escaping religious prejudice here in Ethiopia could simply lead to racial prejudice in their long-lost ‘homeland.’

These narratives are linked by parallels of history and suffering, but above all the enduring belief that there exists a perfect land, where life can be pure again and the grass is always greener. And yet the two men also show it’s possible to plant a foot in both worlds, to have more than one identity at the same time. ‘We are here, citizens of Ethiopia, but by blood we are citizens of Israel,’ says Eshetu as he rises from his desk to show me out. ‘Now I’ve been here so long I am Ethiopian by nature, but still I have Jamaican roots,’ echoes Donald, standing in his small garden. ‘You must always know your roots, otherwise you lose yourself.’ He inspects a leaf on his mango tree. ‘That’s what Bob Marley said.’