Published in Bookanista

July 2023

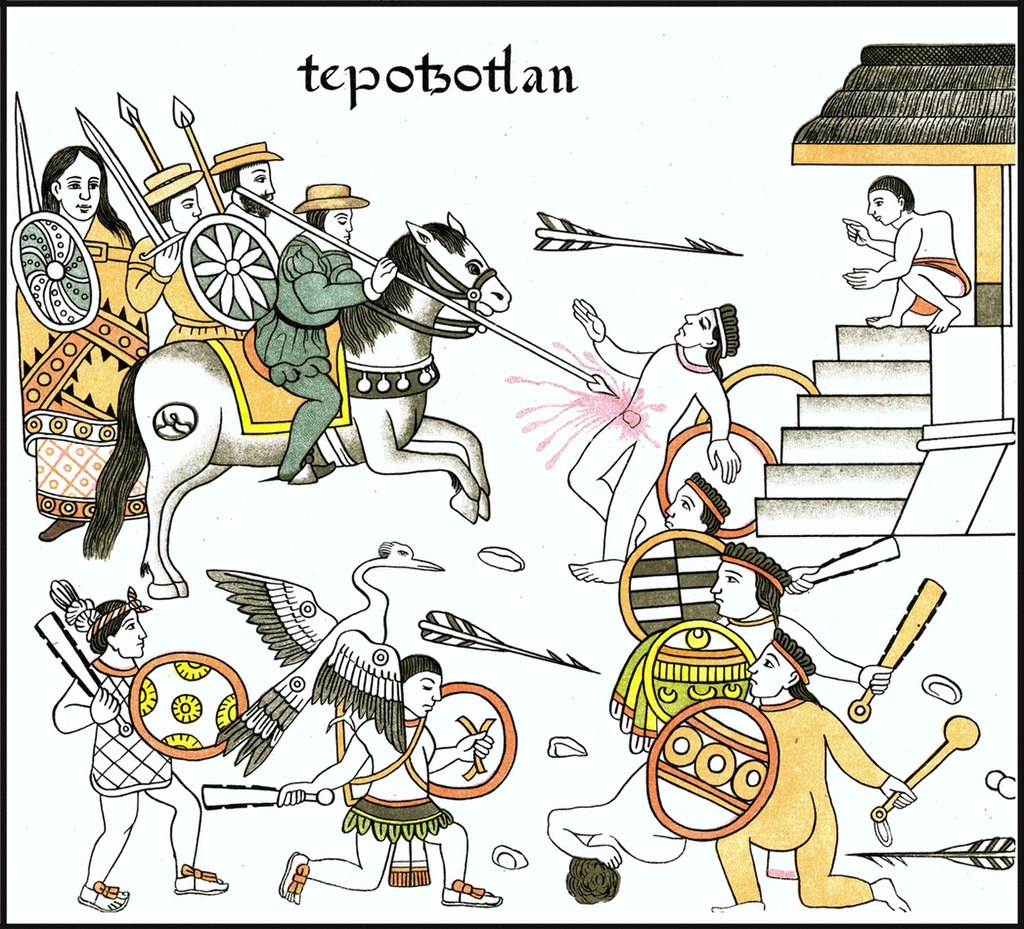

In the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, an Indigenous 16th-century chronicle of the conquest of Mexico, frequently depicted is a young woman with black hair. Dressed in a long skirt and a richly patterned blouse, she stands at the right-hand side of conquistador Hernán Cortés. She seems to be listening intently. Sometimes her finger is raised, as if she is explaining something. This is the figure known variously as La Malinche, Malintzin, Doña Marina or even La Llorona, ‘the Weeping Woman’.

Born around 1500 in the Valley of Mexico, La Malinche was an ethnic Nahua – one of the many subject peoples of the Aztec empire. As a girl she was enslaved and sold to the Mayans in the east, so she grew up with a command of two distinct languages: Yucatec Mayan and Nahuatl, the language spoken by the Aztecs. Given by her Mayan masters as a gift to the invading Spaniards, she made herself instrumental to Cortés, who recognised her potential as an interpreter. By enabling communication from Spanish to Yucatec Mayan (which some Spaniards spoke already), and Yucatec Mayan to Nahuatl, she was the linguistic missing link between Cortés and the Aztec emperor Moctezuma II. Vastly outnumbered, the Spanish depended on diplomacy and guile in order to enter, and eventually destroy, the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan. Without La Malinche, it is unlikely that Cortés could have achieved this.

Her motivation, seemingly, was simple: revenge. Her people had been oppressed by the Aztecs for centuries, not only forced to pay them tribute but also to provide food for their gods, in the form of human captives sacrificed at their temples. Like others under the Aztec yoke, La Malinche hoped to use these violent foreign wanderers, with their horses, guns and steel, to liberate her people. It was not to be that way. The apocalypse that followed did not stop at Tenochtitlan: all the cultures of Central America, including the Nahua, were rapidly to be destroyed by Spanish imperialism.

Another motive for La Malinche, surely, was survival. A woman enslaved in an age where life was expendable, she used the only advantage she had: her knowledge of different tongues. As a trafficker between worlds, she rose to a position of influence. She also became Cortés’s mistress and the mother to his son, apocryphally the first mestizo, or mixed-race, child.

Her legacy in Mexico today is complex and divisive. Over the centuries she has been denigrated as the great betrayer – the pejorative term malinchista means a person who sells out Mexico – but she is also celebrated as a feminist icon. Some have seen her as a powerful woman with agency and intelligence; others as a victim who was almost certainly raped. She can be glimpsed in the murals of the socialist painter Diego Rivera, who interpreted the Aztec struggle against the Spanish through a Marxist lens, and in the sartorial style of his wife Frida Kahlo. She has passed from history into myth – and into the supernatural.

The Weeping Woman is a ghost sighted throughout Mexico, wandering the countryside crying for her lost children. Some say these children were drowned in a flood; others believe they represent the millions of Indigenous lives destroyed by smallpox and genocide during the Spanish invasion. The story of La Malinche attached itself to this tragic spirit – which may itself be a folk memory of an older Aztec deity – so the two are now inseparably linked. Sometimes cursed, sometimes celebrated, she is embedded in the DNA of Mexico’s mixed culture.

She is also at the heart of my novel Red Smoking Mirror. An alternate history set in a world in which Moors from Islamic al-Andalus, rather than Christians from Spain, crossed the sea to the New World – or ‘New Maghreb’ – in 1492, the story revolves around the love between her and a Moorish-Jewish merchant, Eli Ben Abram, as the coexistence between their two cultures comes under threat. She is not the same La Malinche who threw her lot in with Cortes, resembling her in many ways but diverging in others, so I gave this fictional version of her a new name: Malinala.

As for Eli Ben Abram, who led the first Moorish ships across the sea, he is only slightly based on the ruthless, rapacious Genoan sea-captain who is remembered every year on Columbus Day. Hopefully his character is eminently more likeable; although Eli, as will be seen, has his shadows too. And an element of Cortés – sadly and inevitably – is also present in the novel, in the figure of the fundamentalist general Benmessaoud. But despite the similarities of their archetypal roles – interpreter, navigator, destroyer – all three characters are their own, untethered from historical fact. They are less portrayals of actual people than imaginative echoes.

After the conquest, as Tenochtitlan’s great stepped temples were pulled down and Mexico City’s cathedral erected from the same stone, the real-life La Malinche settled in a nearby town. Her son Martín was born a year after the Aztecs fell – nicknamed simply El Mestizo for his mixed ethnicity – and she later married another Spaniard who gave her a daughter, María. Cortés used her services as an interpreter again in 1524, to help crush a rebellion in what is now Honduras. She died around 1529, not yet thirty years old.

In my early twenties I travelled very slowly through Mexico, inadvertently tracing the route that the Spaniards and La Malinche took, from the Yucatán Peninsula to the heart of Mexico City. My memories of those months, and the ruins of those civilisations, were the imaginative soil from which this novel grew. I hope that the character of Malinala adds another layer to La Malinche’s multifaceted myth, and that the Weeping Woman one day finds her children.