First published in Italian in Corriere della Sera

June 2018

The Levanter wind is born at sea, rising in the great womb of the Mediterranean, conceived when the pressure is high off the south-eastern tip of Spain. Its origins are often murky, its first tentative steps on the water veiled by cloud, mist and rain. This infant does not yet have a name. Around the Balearic Islands it is still just a breeze, drying the sweat on sun-bronzed bodies on the beaches of Mallorca and Ibiza, but as it streams to the south-west it picks up warmth and speed. Other winds prophesy its arrival: offshore breezes ruffle the waves along the Murcian coast, and far to the north, in the Rhone Valley, the legendary Mistral stirs, rising as if in tribute to its seafaring cousin.

By the time it hits the Alboran Sea – the westernmost part of the Mediterranean, which separates North Africa from the Iberian Peninsula – the Levanter has come of age, maturing into a powerful flow roaring westwards along the coast of Spain. Weather satellites warn of its coming. The captains of yachts and sailing ships hurry for safe harbour. The Barbary apes on the Rock of Gibraltar take shelter, perhaps in the same caves that our Neanderthal predecessors did 40,000 years ago. Did the Levanter blow for them too, whipping back their shaggy hair and animal-skin clothing? There is every reason to think it did: for residents of the Rock today – that awkward remnant of the British Empire stranded a thousand miles from home, which Spaniards so love to hate – Gibraltar and the Levanter are inextricably bound together, each one unimaginable without the other.

Gibraltar is where the Levanter is at its most dramatic. It can reach gale force here, grounding flights and wreaking havoc on one of the world’s busiest shipping channels, straining to tear the confident Union Jacks from their flagpoles. But its most famous effect is the iconic ‘banner cloud’ that forms on the leeward side of the Rock, a thick white plume that hangs motionless, as if tethered to the summit. Depending on atmospheric conditions these cloud effects take different forms – they can resemble ethereal cruise ships, UFOs or great white whales, mushrooms or billowing tablecloths, volcanic smoke or driven snow – but all of them are a result of humidity being stripped from the air as the Levanter thunders west, breaking free of the stultifying confines of the Mediterranean. At last the wind pours through the Strait of Gibraltar like water draining through a plughole, vanishing (if winds can vanish) into the much vaster expanse of what medieval Arabic sailors knew as the Sea of Darkness.

It’s a suitable name for the Atlantic, for this is a deeply mythical place. To the Greeks and the Romans this narrow strait, where Europe almost touches Africa, was the edge of the known world, defined by the ancient boundary markers of the Pillars of Hercules – the Rock of Gibraltar to the north and Jebel Musa to the south, on the Moroccan coast – which formed the westernmost limit of the hero’s labours. One legend says he travelled here to steal the Cattle of Geryon from the Garden of the Hesperides, while another says he used his strength to smash through what was then Mount Atlas to connect the Mediterranean with the Atlantic, leaving two rocky stumps behind. According to popular belief the pillars were once inscribed with the words ‘Non plus ultra’, meaning ‘nothing further beyond’. Charles V of Spain dropped the ‘non’ and adopted it as his personal motto after a certain Genoan sailor made landfall in the New World; the words appear in Spain’s coat of arms, along with two symbolic pillars flanking its shield and crown.

But centuries before Columbus’s ships sailed west, with the Levanter behind them, this all-important stretch of water was spanned by another culture. In 711 AD the Moorish army of Tariq ibn-Ziyad crossed from North Africa and quickly defeated the Visigothic kings of Spain. Christian dominion collapsed; within a few years, Berbers and Arabs controlled the Iberian Peninsula from the Mediterranean to the Pyrenees. The Islamic presence in Spain lasted for eight hundred years (in a peculiar twist of history the last Moorish king was expelled from Granada in 1492, the same year that Columbus sailed), and its influence in Spanish culture is still clear today, from Andalusian architecture to the cadences of flamenco. The modern Spanish language is richly steeped in Arabic words, as are place-names across the country: Cadiz derives from Qadis, Seville from Ishbiliya, Toledo from Tulaytulah, Andalucia from al-Andalus. Gibraltar itself owes its name to the first Islamic conqueror: the Moors knew it as Jabal Tariq, or Tariq’s Mountain.

Where does the Levanter come into this? I’ll admit that my vision of history is a hopelessly romantic one, but the sight of that banner-like cloud – a pennant fluttering on the lance of a medieval knight – recalls the glories of Al-Andalus and the long Reconquista, when kingdoms and caliphates fought for control; I imagine the Moorish invaders saw it floating above the new land like the white flag of surrender. A connection can also be found in the name, as the novelist Paulo Coelho notes in The Alchemist: ‘The wind began to pick up. He knew that wind: people called it the levanter, because on it the Moors had come from the Levant at the eastern end of the Mediterranean.’ This may not be geographically accurate – the Moors came from the south, not the east – but the culture they brought with them pulled Spain away from the Christian west and into an eastern orbit for the next eight centuries. Does the blowing of this wind carry a memory of this time, linking the westernmost part of Europe with the Islamic east? I like to think it does.

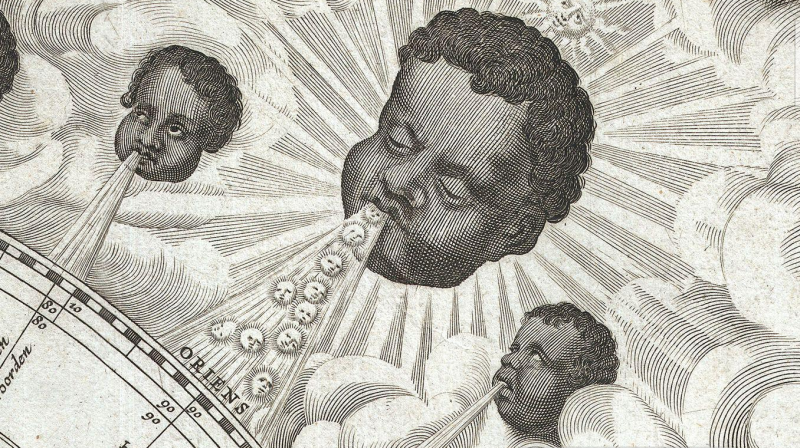

The Levanter is the wind of the sun, flooding the strait with warm air and causing temperatures to rise on both sides of the sea. Its name derives from the Spanish ‘levantar’, ‘to rise’, because it comes from the direction of the dawn; an alternative name is the Solano, which also has solar connections. On one seventeenth-century wind-rose, rather than the usual blond-haired cherub puffing out a blast of air, it is depicted as a dark-skinned African face exhaling a shower of tiny suns over the world. But in common with other great named winds, the easterly Levanter/Solano is mirrored by its opposite: the westerly Poniente, which brings Atlantic coldness instead of Mediterranean warmth, and takes its name from the verb ‘poner’, ‘to lie down’ or ‘to set’. The Strait of Gibraltar is caught in an aeolian tug-of-war between opposing influences from the east and the west, forces that have shaped its cultures for over a thousand years.

Europe has dozens of named winds, and in 2016 I set out to walk the routes of four of them: the Helm of northern England, the Bora of the Adriatic, the Foehn of the Alps, and the Mistral of the South of France. The Levanter blows at sea and I am a walker, not a sailor, so I did not follow its path. I can only imagine sailing west with the wind of the sun at my back, midway between Europe and Africa, rushing through the Pillars of Hercules into the Sea of Darkness.