Published in Waterfront

December 2019

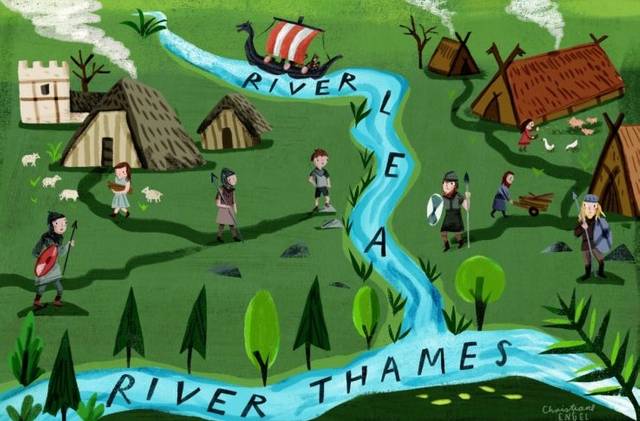

The River Lea still has the sense of being a border zone. Flowing 50 miles south east from the Chilterns to the Thames, it forms a natural barrier to London’s East End, separating Hackney and genteel Stoke Newington from ex-industrial Walthamstow and the wilds of Epping Forest. The marshes lying in between feel slightly like a no man’s land. Woodsmoke drifts from painted houseboats. Hasidic families feed the swans. Feral ring-necked parakeets zoom along the banks at dusk. Different communities meet, and mix, a bit easier here than elsewhere.

The river is also the boundary between the city and the countryside. Travelling several miles upstream – whether by foot, bike or boat – takes you from London suburbs and into rural Hertfordshire, a bucolic English landscape of water meadows, woods and fields. This is the meeting of two worlds. But perhaps the idea of the Lea as a frontier should not be so strange, because, once upon a time, it was. In the 9th and 10th centuries this river – a broader, marshier and more meandering waterway back then – was the border between two cultures: the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings.

“First concerning our boundaries: up the Thames, and then up the Lea, and along the Lea to its source, then in a straight line to Bedford, then up the Ouse to Watling Street”, says the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum, written around AD 880. With these words, two warring monarchs – King Alfred the Great of Wessex and King Guthrum of the Danes – formally divided England into spheres of influence: Anglo-Saxons in the south and west (and in the northern kingdom of Northumbria) and Danes in the north and east. The Danish part of England was recognised as the Danelaw.

The treaty was signed to settle a conflict that had raged since 865, when a large Danish Viking force landed on the east coast. The Great Heathen Army, as it became known, proceeded to lay waste to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria, capturing the city of York and turning it into their capital, Jorvik. Soon only the kingdom of Wessex remained undefeated. Alfred paid off the invaders through a time-honoured system of bribes called Danegeld, basically a Dark Ages form of protection money. The Vikings discovered that it was easier to extort regular payments of treasure than carry on pillaging. East of the Lea they settled down, built villages and started farming.

Gazing across the river then – perhaps from what is now Springfield Park, or further south from Hackney Wick towards Stratford and the Olympic stadium – would have meant looking into a foreign country. Beyond the wooded riverbank was a place where the people spoke a different language, obeyed different laws and worshipped different gods. Although there was certainly fear and suspicion, with the threat of raiding and feuding never very far away, the relationship might not have been entirely antagonistic. During the years of coexistence there must have been trade and cultural exchange, cooperation as well as competition. Some scholars think that day-to-day life in the Danelaw was, in many respects, freer and more equitable than on the Lea’s western side. Who knows, perhaps an Anglo-Saxon peasant fishing here in the year 900 might have glanced towards the opposite bank with envy.

While the Danelaw ended in 954 with the death of Eric Bloodaxe, the Viking presence in England did not go away. In fact, in the 11th century the whole country fell under Danish rule, first under Sweyn Forkbeard and then his son Cnut the Great, who famously got his feet wet to prove that he could not turn the tide. Centuries of alternating Anglo-Saxon and Danish rule only came to an end in 1066 with the invasion of the Normans, themselves the descendents of Vikings who had settled in France.

Another landmark on the Lea brings this history to a close. In the grounds of the beautiful Waltham Abbey, on the river’s eastern bank, is a grave said to contain the bones of a man and a woman. He was Harold Godwinson, who fell – according to popular belief – with an arrow in his eye at the Battle of Hastings. She was his wife Edith the Fair, also known as Edith Swan-Neck. It is a curious twist of history that England’s last Anglo-Saxon king should be buried on the eastern – Danish – side of the watery border that once divided, as well as joined, two peoples. And Edith’s graceful namesakes still glide up and down the river today, as if in memory.The River Lea still has the sense of being a border zone. Flowing 50 miles south east from the Chilterns to the Thames, it forms a natural barrier to London’s East End, separating Hackney and genteel Stoke Newington from ex-industrial Walthamstow and the wilds of Epping Forest. The marshes lying in between feel slightly like a no man’s land. Woodsmoke drifts from painted houseboats. Hasidic families feed the swans. Feral ring-necked parakeets zoom along the banks at dusk. Different communities meet, and mix, a bit easier here than elsewhere.

The river is also the boundary between the city and the countryside. Travelling several miles upstream – whether by foot, bike or boat – takes you from London suburbs and into rural Hertfordshire, a bucolic English landscape of water meadows, woods and fields. This is the meeting of two worlds. But perhaps the idea of the Lea as a frontier should not be so strange, because, once upon a time, it was. In the 9th and 10th centuries this river – a broader, marshier and more meandering waterway back then – was the border between two cultures: the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings.

“First concerning our boundaries: up the Thames, and then up the Lea, and along the Lea to its source, then in a straight line to Bedford, then up the Ouse to Watling Street”, says the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum, written around AD 880. With these words, two warring monarchs – King Alfred the Great of Wessex and King Guthrum of the Danes – formally divided England into spheres of influence: Anglo-Saxons in the south and west (and in the northern kingdom of Northumbria) and Danes in the north and east. The Danish part of England was recognised as the Danelaw.

The treaty was signed to settle a conflict that had raged since 865, when a large Danish Viking force landed on the east coast. The Great Heathen Army, as it became known, proceeded to lay waste to the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria, capturing the city of York and turning it into their capital, Jorvik. Soon only the kingdom of Wessex remained undefeated. Alfred paid off the invaders through a time-honoured system of bribes called Danegeld, basically a Dark Ages form of protection money. The Vikings discovered that it was easier to extort regular payments of treasure than carry on pillaging. East of the Lea they settled down, built villages and started farming.

Gazing across the river then – perhaps from what is now Springfield Park, or further south from Hackney Wick towards Stratford and the Olympic stadium – would have meant looking into a foreign country. Beyond the wooded riverbank was a place where the people spoke a different language, obeyed different laws and worshipped different gods. Although there was certainly fear and suspicion, with the threat of raiding and feuding never very far away, the relationship might not have been entirely antagonistic. During the years of coexistence there must have been trade and cultural exchange, cooperation as well as competition. Some scholars think that day-to-day life in the Danelaw was, in many respects, freer and more equitable than on the Lea’s western side. Who knows, perhaps an Anglo-Saxon peasant fishing here in the year 900 might have glanced towards the opposite bank with envy.

While the Danelaw ended in 954 with the death of Eric Bloodaxe, the Viking presence in England did not go away. In fact, in the 11th century the whole country fell under Danish rule, first under Sweyn Forkbeard and then his son Cnut the Great, who famously got his feet wet to prove that he could not turn the tide. Centuries of alternating Anglo-Saxon and Danish rule only came to an end in 1066 with the invasion of the Normans, themselves the descendents of Vikings who had settled in France.

Another landmark on the Lea brings this history to a close. In the grounds of the beautiful Waltham Abbey, on the river’s eastern bank, is a grave said to contain the bones of a man and a woman. He was Harold Godwinson, who fell – according to popular belief – with an arrow in his eye at the Battle of Hastings. She was his wife Edith the Fair, also known as Edith Swan-Neck. It is a curious twist of history that England’s last Anglo-Saxon king should be buried on the eastern – Danish – side of the watery border that once divided, as well as joined, two peoples. And Edith’s graceful namesakes still glide up and down the river today, as if in memory.

Illustration by Christine Engel